I have been thinking about Foucault a lot lately because … [gestures broadly at world]

As a philosopher Foucault gave voice to a general uneasiness that many may feel when confronted with large scale utilitarian plans. At times it can be helpful to stare into and acknowledged this uneasiness. While, from my perspective, Foucault did not really give us any real solutions to that angst, he did succeed in putting into words the dangers of overly obtrusive and controlling measures aimed at ensuring the public good. However, awareness of those dangers should not lead us into despair. There is hope. There is a way to confront these challenges and allow them to move us towards freeing beauty and truth.

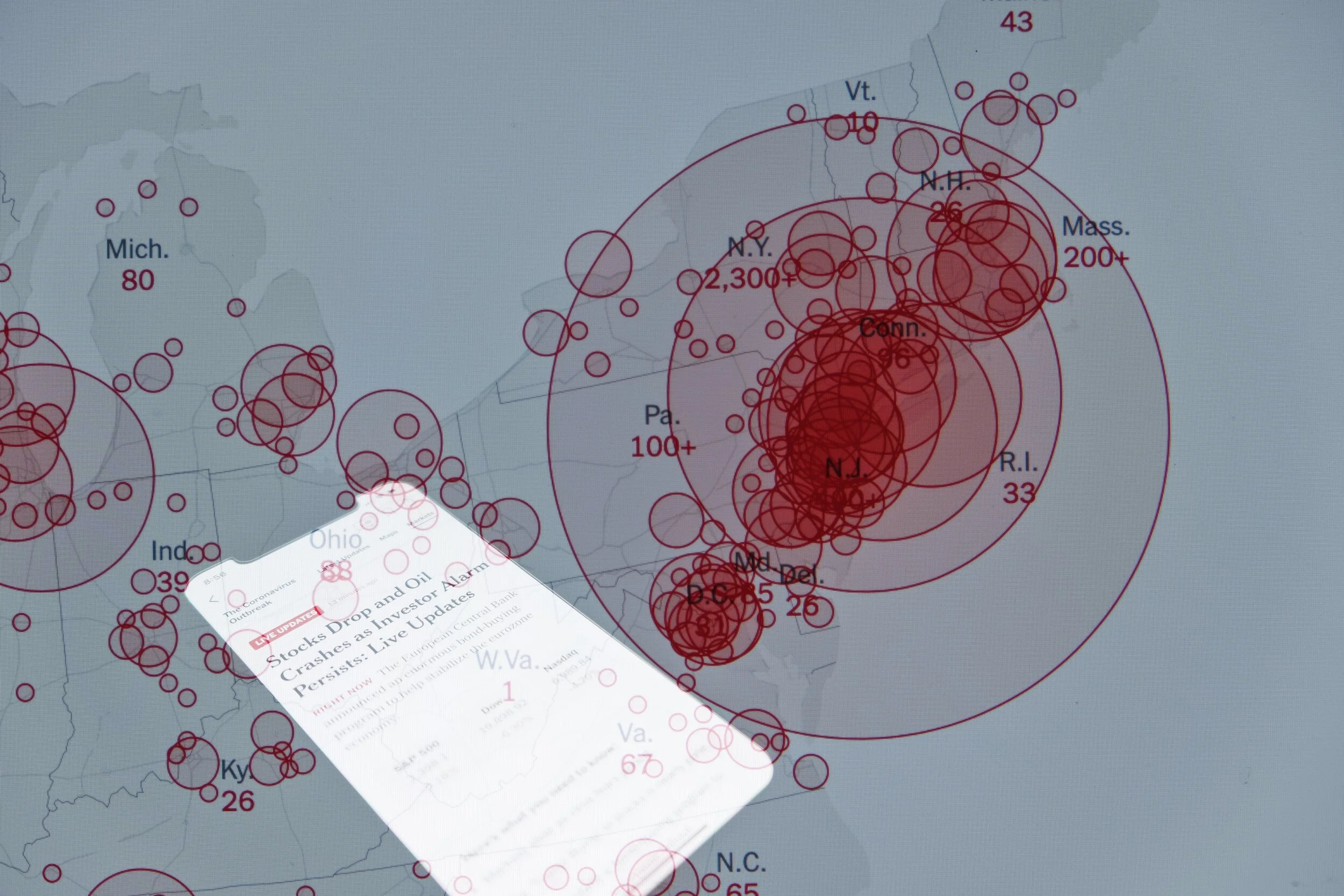

For those of you not familiar with his work, Foucault uses a quarantine analogy to analyze the many restrictions, inconveniences, and invasions of privacy one would undergo in order to prevent the spread of a threat. Even before the pandemic, there was an eerie truth to much of what he says. Foucault describes the power of an un-manned machine. The aim of this power is to “strengthen social forces – to increase production, to develop the economy, spread education, raise the level of public morality; to increase and multiply” (172). Individuals are directed towards the aim of the power in question through an “infinitely minute web of panoptic techniques” (183). The individual is controlled by an uncertain awareness that they might be observed without ever having the certainty that they are in fact being observed. This creates what Foucault describes as an “indefinite discipline: an interrogation without end” (186). Yes, when I talk about Foucault it feels a bit like this…

The mechanisms are designed to increase the utility of the individual using flexible and invisible methods of control. The individual eventually adopts a role within the panoptic machine. The roles of power are taken by interchangeable individual persons. It is the role that holds power not the person. The person assuming the role becomes the “principle of his own subjections” by defining himself by the role (168). This is a natural tendency.

Foucault evokes an unsettling feeling, because so much of what he says can be seen at play within various institutions. The machines of power described by Foucault are all guided by utilitarian aims. As such, man is valued based on utility. As Foucault suggests, “the disciplines function increasingly as techniques for making useful individuals” (174). Pope St. John Paul II was deeply aware of this tendency to utilize individuals. In one of his encyclical letters he states:

“If no one acknowledges transcendent truth, then the force of power takes over, and each person tends to make full use of the means at his disposal in order to impose his own interests or his own opinion, with no regard for the rights of others. People are then respected only to the extent that they can be exploited for selfish ends. Thus, the root of modern totalitarianism is to be found in the denial of the transcendent dignity of the human person, who as the visible image of God, is therefore by his very nature the subject of rights which no one may violate. (66)”

Thus, the only way out of the Panopticon is to avoid defining oneself or others by their role or any other utilitarian standard. One must continuously seek to see the inherent, transcendent, dignity of each person acting as a person possessing dignity and their own will. A Christian is freed by transcendent truth and knowledge of God. One who seeks to align their actions with this freeing truth is saved from the madness of attempting to please an interchangeable unmanned machine.

Blissful freedom.

This freedom is perhaps even more apparent and relevant now. Under the current crises many have been tossed from or had to redefine their role in society. People are losing jobs. Existing jobs are transforming. Educational institutions were forcibly reshaped overnight. Society has been tossed suddenly into a new state. Yes, there is a lot of suffering right now. There is a lot of need that needs to be addressed. However, there is also good in this change. There is more time for family. People are looking for and sharing creative outlets. People are freely offering up what they can to support others in need. As a society we are celebrating people who work hard to support the infrastructures we all rely on.

Our collective gaze has been forced out of the drudgery of the every day. The question is where to direct it now? There are many attempting to direct that gaze down a path of fear. I do not know what is to come in the next few months, when these social isolation measures will end, or what will be of the economy when we get to the other side. I do know that Jesus is a tangible reality in my life; God is with us. That reality will continue no matter what shifts around us and that, my friends, is the way out of the Panopticon. Any other thing that might attract our gaze at this moment is transitory and will not hold the stability needed. In looking to and for Christ, we learn how to live. We learn what to love. We learn what to let go of. Most importantly, we experience love. Love beyond humanly defined roles, achievements, or accumulation. All-encompassing love based on who each of us was created to be.

Works Cited

Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism.” McLaughlin, Becky and Bob Coleman. Everyday Theory: A Contemporary Reader, edited by Becky McLaughlin and Bob Coleman. Pearson, 2005. pp. 163-186.

John Paul II. Encyclical Letter “Centesimus Annus” (Hundredth Year): Of the Supreme Pontiff John Paul II, On the Anniversary of Rerum Novarum. Pauline Books & Media, 1991.